At first, you might be thinking, what does design have to do with liberation? You might feel a tinge of discomfort come over you, and a sigh of, ‘Is nothing safe from wokeness?’ You’d be partially right.

As our critical thought processes evolve, as binaries and ceilings become more expansive, we are forced to reckon with the pervasive, insidious nature of the oppressive, exploitative, white supremacist, capitalist, heteronormative, patriarchal structures we have all been indoctrinated into, voluntarily... and not.

Design Is Never Neutral

Every design decision reflects values. When a building has stairs but no ramp, that’s a design decision that values able-bodied access over disabled access. When an algorithm uses zip code as a feature, that’s a design decision that encodes historical segregation. When a survey only offers ‘male’ and ‘female’ options, that’s a design decision that erases non-binary people.

Traditional design thinking treats these as neutral choices—or worse, as ‘edge cases’ to be handled later. Liberatory design recognizes that every choice has politics, and that ‘neutral’ usually means ‘defaulting to the perspective of people with power.’

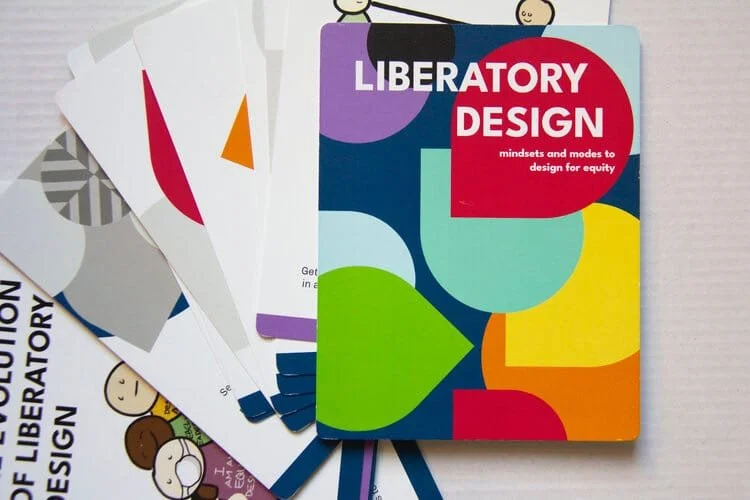

Defining Liberatory Design

‘Liberatory Design is an evolution of the design thinking methodology. It’s an approach to problem solving that helps people translate their values of equity into a tangible process.’ It centers those most impacted by design decisions and aims to disrupt rather than replicate existing power structures.

Traditional design thinking assumes a neutral designer and a universal user. Liberatory design asks: Who is designing? For whom? With what assumptions? And most importantly: Does this design liberate or constrain? Does it expand possibilities or limit them? Does it empower people or control them?

Putting Liberation into Practice

Liberatory design isn’t a checklist—it’s a practice. It requires ongoing reflection on our own positionality: What assumptions am I bringing? Whose perspective am I missing? How might my own privileges blind me to certain impacts?

It requires genuine partnership with communities—not extractive user research where we take insights and leave, but collaborative design where affected communities have real power over outcomes. It requires willingness to cede control, to be led by those most impacted rather than those with the most credentials.

The goal isn’t a better product for the people; it’s a better process with the people. And that process should build power, build capacity, build relationships—not just build products. Liberation isn’t something we design for others. It’s something we design alongside them.